Revenue: the money coming in

When you’re thinking about the growth of your company, or talking to investors about valuations, revenue is often what matters most.

Here we’ll cover:

- Subscription-based revenue

- Revenue flow concepts

- Tracking churn and retention

- Thinking about the timing of revenue

- Thinking about the value of a given customer to your business

Subscription-based revenue

For subscription-based businesses, you can slice revenue a few different ways, generally in terms of whether the revenue recurs.

Monthly recurring revenue (MRR)

MRR is the total amount of money you receive from your customers each month, on an ongoing basis. If you have 100 customers, each subscribed at a price of $100/month, you have an MRR of $10,000 (100 * 100). New and churned customers aside, at any point in time your MRR effectively is the size of your business.

Annual recurring revenue (ARR)

Same as MRR, but annualized. You can switch back and forth between MRR and ARR by multiplying or dividing by 12 months. Many businesses will talk in terms of ARR, because it’s more common to think of the size of a company in terms of its annual revenue rather than its monthly revenue (e.g., it’s more common to talk about a $10m-per-year company than a $800k-per-month company). It’s worth clarifying that you can still track ARR on a monthly basis, and have a monthly model tracking ARR, which may vary each month (ideally by increasing).

Average contract value (ACV)

ACV is the average amount that a customer pays you each month. Unhelpfully, ACV is also known as average revenue per account (ARPA) or average revenue per user (ARPU).

- ACV is more commonly used for larger customers.

- ARPA is used more in self-serve settings.

- ARPU is used when the customer is an individual rather than a business.

ACV is calculated like so:

Monthly recurring revenue MRR / number of customers for that month.

One-off revenue

Businesses that don’t rely on subscribers typically make one-off revenue. If you make $10,000 in sales from 100 customers in a given month, you make $10,000 in that single month. If you want to make $10,000 again the next month, you have to find 100 new customers. But some subscription businesses will also have an element of one-time revenue, such as one-time consultation services.

Revenue flow concepts

In the same way that you can track your customer numbers by thinking about customer flows, you can keep of track your recurring revenue by thinking about revenue flows.

Average sales price (ASP)

ASP is the average price for any new subscriptions in a given month. ASP can differ from your annual contract value (ACV) for several reasons (for example, if you change your subscription pricing over time).

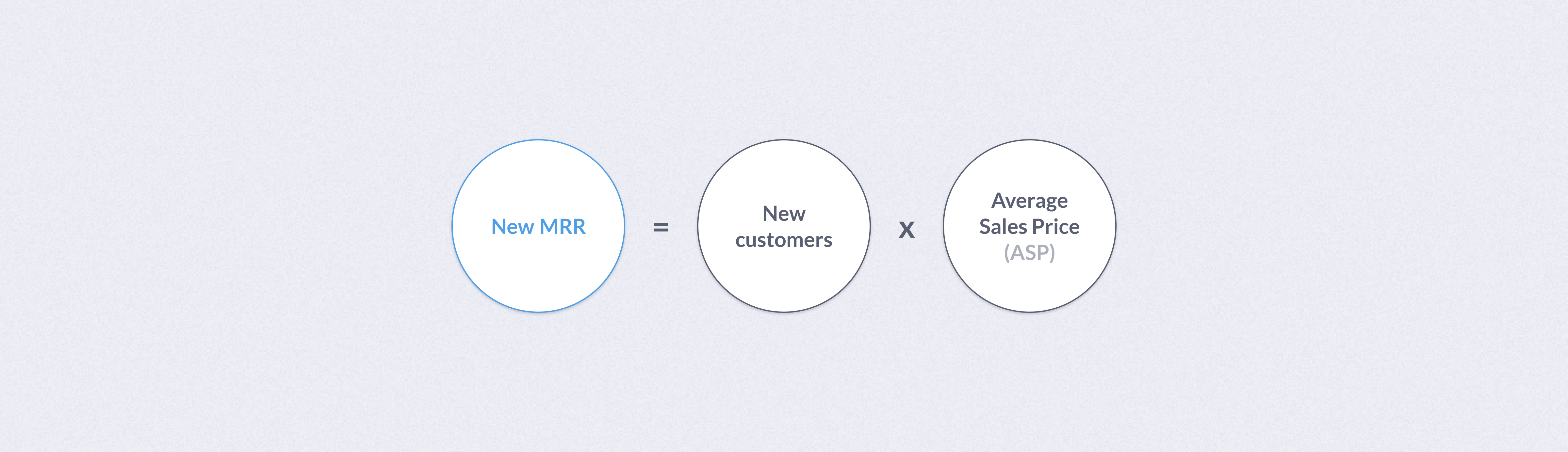

New monthly recurring revenue (New MRR)

New MRR is the amount of recurring revenue you add in a given month.

You can forecast new MRR as:

New MRR = new customers * average sales price (ASP).

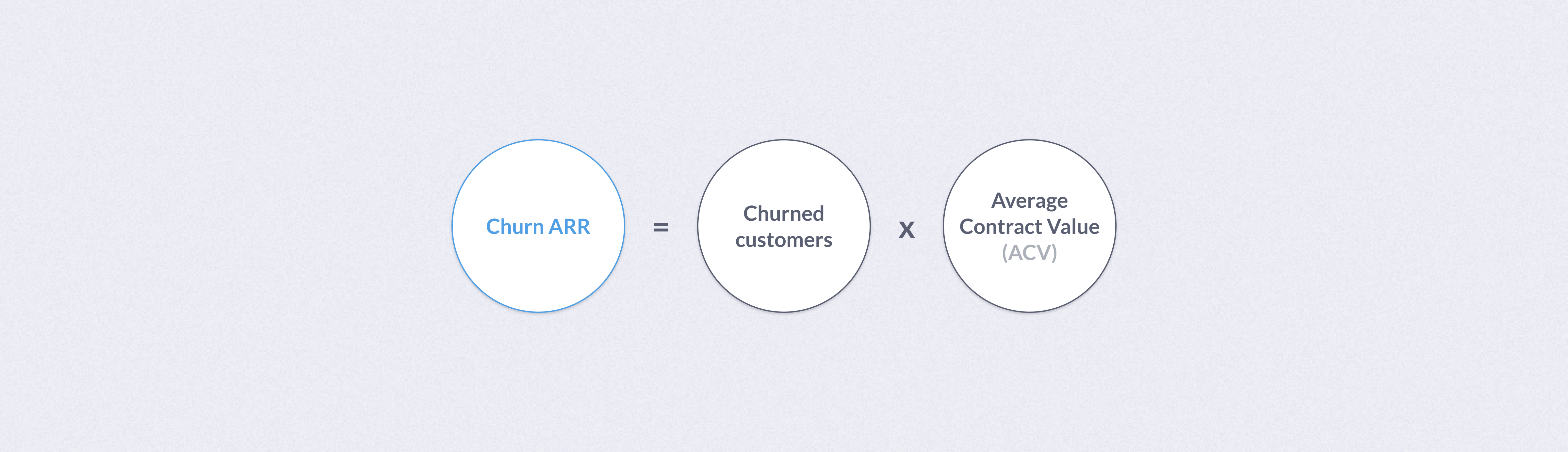

Churn annual recurring revenue (Churn ARR)

Churn ARR. The amount of recurring revenue you lose in a given month because of churning customers. Calculated as the sum of the subscription price for all of the customers you lose in a month.

You can forecast churn ARR as:

Churn ARR = churned customers * ACV

Expansion ARR

Expansion ARR is when your existing customers increase the amount they pay each month. Expansion usually happens via one of two routes, depending on how you price your product:

- If you have a higher priced product tier, a customer can expand by upgrading.

- If you have variable pricing, a customer may use more units in one month than before (for example by adding more user accounts for new hires).

Expansion ARR is calculated by taking the ARR you added from expansion in a given month, summed across all of your customers.

Contraction ARR

Contraction ARR refers to the reduction of revenue when your customers reduce the amount they pay each month. Similar to expansion, customers contract either by:

- Downgrading to a lower-priced product tier.

- Using fewer units (e.g., reducing the number of user accounts).

Contraction ARR is calculated as the ARR lost to contraction in the month, summed across all of your customers.

Tracking churn and retention

Some customers will remain loyal to the cause until the end. The feckless and unlucky will churn.

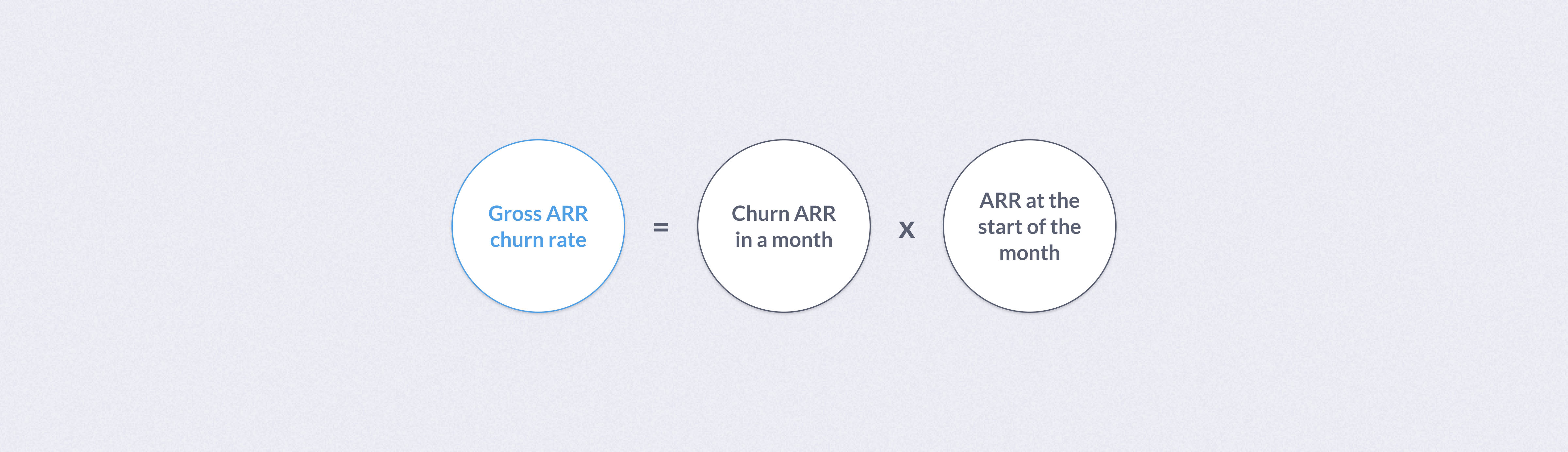

Gross ARR churn rate

To help you understand if your customer churn is high or low, you can convert the number of churned customers into a customer churn rate. However, what if you offer subscriptions at different prices? Losing 10 customers from your highest-priced plan is worse than losing them from your lowest-priced plan. To put these numbers on an even footing, you can look at the proportion of your recurring revenue lost in a given month, or your ARR churn rate.

Gross ARR churn rate = Churn ARR in a month / ARR at the start of the month

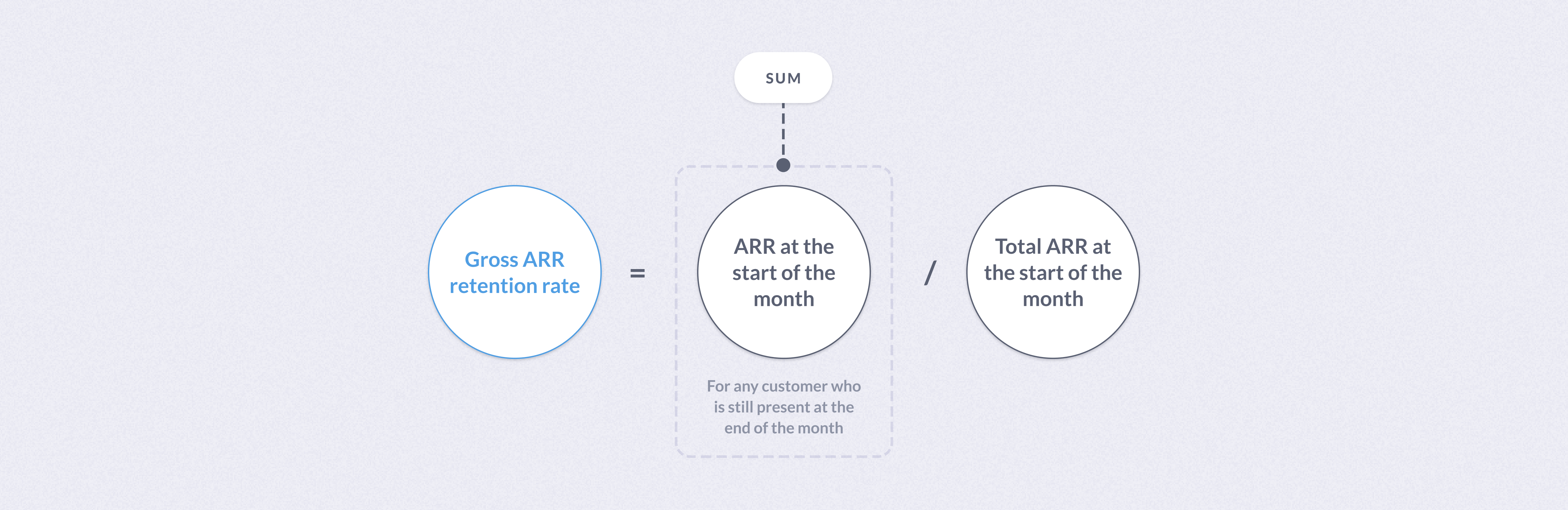

Gross ARR retention rate

Gross ARR looks at the ARR retained during the month. Gross ARR retention rate is effectively the opposite of gross ARR churn rate. The gross ARR retention rate (usually) ignores the effect of any expansion or contraction (often because some definitions of gross ARR churn do include ARR contraction).

Gross ARR retention rate = Sum (ARR at the start of the month, for any customer who is still present at the end of the month) / total ARR at the start of the month

or

Gross ARR retention rate = 1 - gross ARR churn rate

Net ARR churn rate.

Net ARR churn is a similar measure to gross ARR churn, but it rolls in the effects of expansion and contraction. Imagine you have ten customers. Two of them churn, leaving you with eight customers. But at the same time, those eight remaining customers’ ARR expands because they upgrade their subscriptions. In this situation, overall your ARR from that original group of customers may actually increase, because the expansion ARR more than offsets the churn ARR you lost. Net ARR churn captures this concept by rolling churn, expansion and contraction into one measure.

Net ARR churn rate is calculated as:

(Churn ARR in a month + Contraction ARR in a month - Expansion ARR in a month ) / ARR at the start of the month

Note that expansion ARR has the opposite sign to churn ARR and contraction ARR because it works in the opposite direction.

Your Net ARR churn rate will be negative if you gain more ARR from expansion than you lose to churn and contraction. Achieving negative ARR churn is the holy grail for subscription businesses because it means that on average, the ARR for any group of customers that sign up will grow indefinitely (subject to known physical laws).

Net ARR retention rate

Again, this is the opposite of the net ARR churn rate. For a given group of customers, it measures how much of their ARR you are left with at the end of the month (or year), once you’ve accounted for churn, contraction and expansion.

Net ARR retention rate = Sum (ARR at the end of the month, for any customer who was also present at the start of the month) / total ARR at the start of the month

or

Net ARR retention rate = 1 - net ARR churn rate

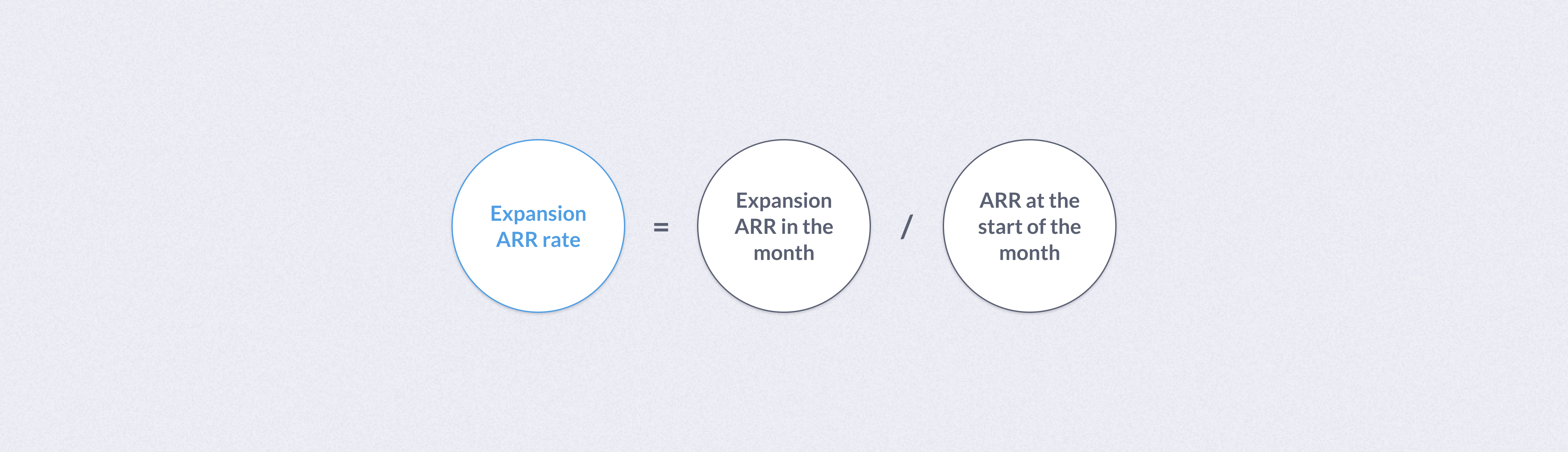

Expansion and contraction rates

The expansion rate is the expansion ARR, expressed as a % of the total ARR at the start of the month. Having expansion of $1,000 is much more impressive if you have an ARR of $10,000 than if you have an ARR of $1,000,000. Hence we traffic in rates. Contraction ARR rate is the same concept.

Expansion ARR rate = Expansion ARR in the month / ARR at the start of the month

and

Contraction ARR = Contraction ARR in the month / ARR at the start of the month

How do you forecast recurring revenue?

Once you’ve forecast customers numbers, you can derive your new ARR and churn ARR:

New ARR = new customers * average sales price (ASP).

and

Churn ARR = churned customers * ACV

You can then estimate your expansion and contraction ARR as:

Expansion ARR = ARR at the start of the month * Expansion rate

and

Contraction ARR = ARR at the start of the month * Contraction rate

Now that you’ve forecast these four elements, you can estimate your total ARR each month by doing another ‘walk forward’:

| Month 1 | Month 2 | Month 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beginning ARR balance | 0 | 10,000 | 20,500 |

| New ARR | +10,000 | +12,000 | +14,000 |

| Expansion ARR | 0 | +1,000 | +1,500 |

| Contraction ARR | 0 | -500 | -500 |

| Churn ARR | 0 | -2,000 | -3,000 |

| Ending ARR balance | 10,000 | 20,500 | 32,500 |

Why not create an ARR forecast directly?

Astute readers may have spotted that you could skip the estimation of your number of customers and estimate your ARR changes directly. For example, you could estimate your churn ARR directly by estimating your average gross ARR churn rate and using that instead of your customer churn rate.

There isn’t a wrong way to do it. We’ve chosen to start with the customer forecast, but you could even work back from your ARR forecast to estimate your customer numbers.

The reason to forecast both customer numbers and ARR is that both are useful. We’ve talked a lot about the usefulness of tracking the amount of money you think you’ll make. But it’s also useful to know how many customers you expect to have. For example, customer forecasts can help with hiring decisions. Your Success team may be a very different size if you anticipate 1,000 customers vs. 100.

The reason to start with the customer forecast is that some numbers are easier to forecast as customer numbers than as ARR dollars. For example, it’s easier (and more believable) to estimate the number of new customers you’ll sign up each month based on the number of visitors who come to your website, than it is to say “I signed up $10,000 in ARR last month so I’ll sign up $12,000 this month.”

Thinking about the timing of revenue

When do you actually count revenue? When you render the service? Or when the cash hits your bank account?

Annual contracts

Under an annual subscription contract, a customer pays you up front for a year. Converting annual contracts to MRR is straightforward: divide the annual contract value by 12 to get the new MRR. Because the contract is annual, the customer cannot churn for at least 12 months, so annual contracts are sometimes offered at a discount in exchange for the guaranteed revenue.

Accounting revenue, and why it won’t (necessarily) add up

As a startup, you’ll probably pay an accountant to track your revenue and send you financial reports each month. If you compare your revenue from your financial statements to your recurring revenue, the revenue numbers won’t match up. This discrepancy is because accountants use different methods to count revenue.

Cash accounting

If you use cash accounting, your accountant will count any money that lands in your bank account in a given month as revenue. This accounting revenue can differ from your recurring revenue for a few reasons:

- If you collect credit card payments through a payments platform, there’s usually a delay between 1) the payment platform charging the customer, and 2) the payment platform depositing that money to your bank account. Which means that subscription charges from one month may show up as the following month’s accounting revenue.

- If you have any annual subscriptions, you’ll usually be paid up front. Accounts will count that money as accounting revenue in the month the payment went through, whereas you’d count it as recurring revenue each month for the duration of the 12-month contract.

Accrual accounting and revenue recognition

If you use accrual accounting, your accountants will use a process called revenue recognition to try to allocate your revenue to the month in which it was earned. That is, the month when your business rendered the service (not necessarily the month when the customer actually paid you). Accrual accounting should track more closely with recurring revenue, but they usually don’t line up perfectly.

Customer lifetime value (LTV)

LTV is a measure of the total revenue you’ll receive from a single customer over their ‘lifetime’ as a subscriber. Knowing the LTV for different customer segments can be helpful in making decisions about how much money to spend acquiring customers.

Imagine you have two customers who both pay $100/month. One sticks around for six months, and the other sticks around for two years. The second customer pays you four times as much as the first.

Calculating LTV for a single customer is simple: you multiply the monthly price by the duration of the customer’s subscription.

There are, however, some challenges to calculating customer lifetime value:

- If a customer hasn’t yet churned, you don’t know how long the customer will stick around for.

- Usually you want to calculate LTV for a group of customers, rather than a single customer. For example you want to compare the value of customers in region A vs. region B.

In practice you get around these challenges by estimating the customer lifetime value (rather than calculating LTV directly). The formula for LTV is:

LTV = average contract value (ACV) / customer churn rate (CCR)

Some LTV formulas modify this to:

LTV = average contract value (ACV) * gross margin / customer churn rate (CCR)

This second LTV formulation accounts for the fact that you spend some of the customer revenue on costs associated with serving that customer during their lifetime.